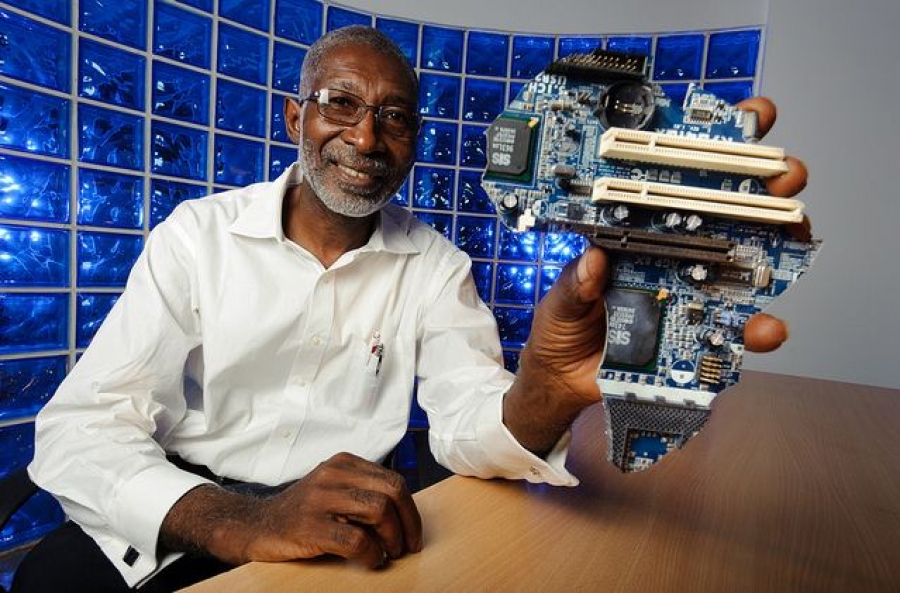

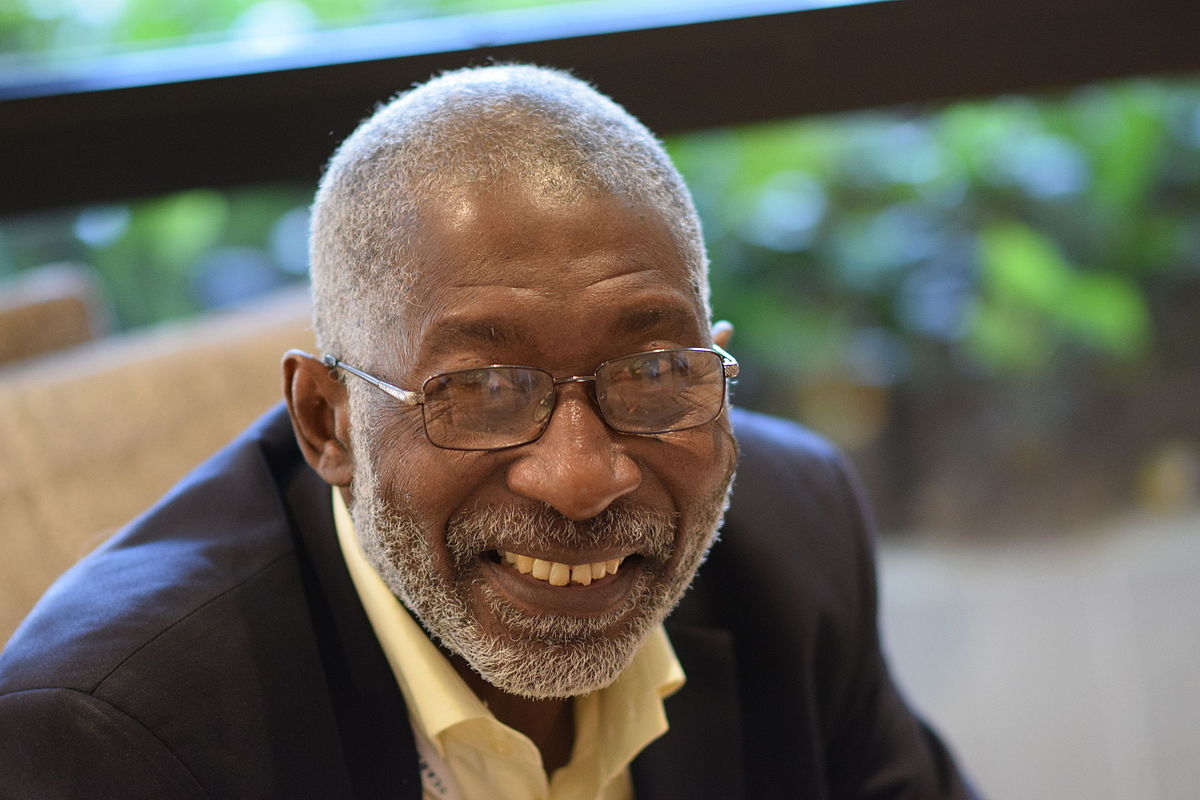

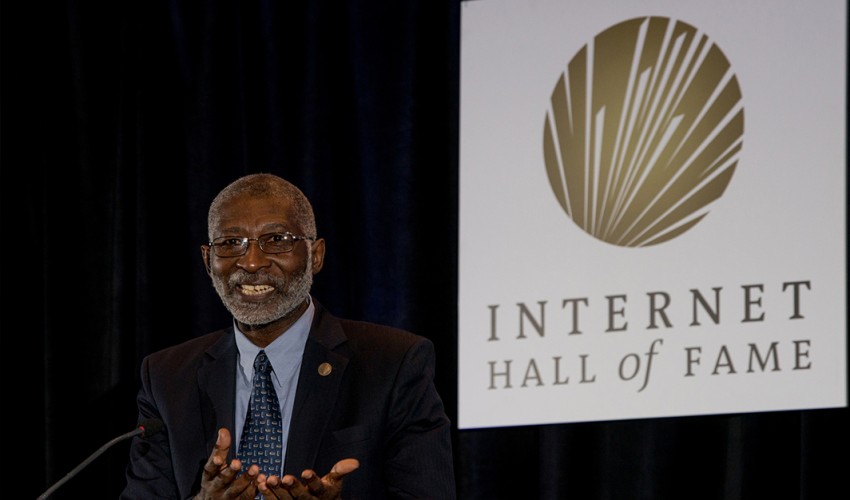

NII NARKU QUAYNOR: AFRICAN FATHER OF THE INTERNET

Did you know that Professor Nii Narku Quaynor, from Ghana, pioneered Internet development and expansion throughout Africa for nearly two decades, establishing some of the continent’s first Internet connections and helping found key organizations, including the African Network Operators Group, to advance Internet connectivity and use in Africa? For his sterling efforts, Dr Quaynor has been inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame. Curtis Abraham went to interview him.

Dr Nii Narku Quaynor’s many achievements include helping to establish the Computer Science Department of the University of Cape Coast (UCC) in Ghana, where he has taught since 1979.

He was also the first African to be elected to the board of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which oversees policies and protocols related to Internet domains and addresses, and served as an at-large director of ICANN for the African region from 2000 to 2003.

Dr Quaynor was also a member of the UN Secretary General’s Advisory Group on ICT, chair of the OAU Internet Task Force, and president of the Internet Society of Ghana. In 2007, the Internet Society awarded him the Jonathan B. Postel Service Award for his pioneering work in advancing the Internet in Africa. In 2012, he was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame.

In this interview, Dr Quaynor talks about his hopes and fears for the future of the Internet in Africa. With African Internet user penetration currently standing at a mere 4.8%, Dr Quaynor warns that “Africa is about to miss a great development opportunity in much the same way Africa lost on the industrial revolution, unless serious and truly committed efforts are made by Africa to address the rapid expansion of the Internet user gap between Africa and industrialized countries.”

Q: What was life like for you growing up in Ghana during the 1950s and 60s?

Life was good growing up in Ghana. My family experienced no particular hardships at the time, although the instability of the coup d’état of 1966 [that overthrew President Kwame Nkrumah’s government] was sufficient for several students to move overseas for education.

I myself left Ghana and went to the US for my university education three years after the coup. It was not because of the coup, however, I was simply following a line of senior brothers who all went overseas for their university education.

Q: What initially excited you about science and technology?

I was the youngest in a family of scientists and although my father did not have a university education, my siblings included an eye surgeon, a dentist, a wood technologist, and a highway civil engineer. Coming from a noted scientific family, my strengths were clearly physics, pure maths, applied math’s, and chemistry at A Level; and scoring 3 as I did at Achimota School. I also admired all my elder brothers who taught me a lot.

Q: Did President Nkrumah’s dream of making science and technology the key to rapid socio-economic development in Ghana have an influence on you?

Yes, but others such as Nelson Mandela also steered my focus towards achieving “techno-liberation”. It’s evident that the lack of technical know-how has literally self-colonized Africa. Like both Nkrumah and Mandela, I am certain that Africa has to own its development processes.

I also learnt from them that any society that lacks highly specialized knowledge, could churn out consumers who are not involved in the supply chain. The liberation and commitment could only have been instilled from the philosophy of liberation leaders like Nkrumah and Mandela.

Q: As a young African in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement in America, you must have experienced an enormous culture shock. What was life like for you?

The culture shock was there but my purpose was to acquire knowledge, so it was easy to adjust. I arrived at Dartmouth College in 1969 when the civil rights movement was bringing about integration at the universities, and naturally I was always among a small group of Africans and African-Americans who faced the challenges of a new intellectual world. So in spite of the racial and social atmosphere during the early 1970s, the academic community encouraged those who wanted education. There was harmony when I studied, and it kept me not only out of trouble but also steered me into help.

Q: You are on record as having said that the Civil Rights struggle in America affected your “orientation” and pan-Africanist ideas: explain.

Yes, it brought attention to Africa’s potential and its desire for participation in the global economy. Naturally, that struggle continued to remind me of my African roots and the fact that I had also become part of the diaspora.

During my time at Dartmouth we were appalled when a well-known scientist, Walter Hermann Schottky, gave a lecture and students protested against his claims on race and intellectual capacity.

This incident reminded us in the Diaspora that only Africans could liberate and develop Africa. That fact alone inspired me to want to help my people in my area of expertise. It planted in me a desire and dedication to struggle to acquire knowledge for the liberation and development of Africa.

Q: Why did you decide to return to Africa?

As one of the first PhDs in computer science on the African continent, and the first in Ghana, I felt obligated to return to establish a department of computer science at the University of Cape Coast (UCC) in 1979. It was necessary to establish a computer science department to provide an alternative at UCC, and secondly to produce newer, more prepared students for the new computer industry of Internet-based solutions. I felt a commitment to Africa’s development in this irreversible ICT revolution.

Q: You have written of your optimism about Africa bridging the digital divide, given the fact that some African societies traditionally used calculating board instruments. Explain?

Africa can bridge the digital divide given its history of strong elements of Information Processing (IP) tools, such as its calculating board instruments. These instruments, like Oware, had supported early African societies with calculations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of up to 10 digits numbers.

A set of calculating boards readily records information. Many Africans were of the view that computing was, generally, a foreign concept – this is not the case. Prior to the advent of Western education, Africans used the board for complex calculations. That board was as powerful as the Chinese abacus that served as the computing instrument for the people of Asia for many years.

Thus, information processing is not foreign to African society, but it has not developed in synch with the rest of the world in more recent times, with the acceleration of new electronic technologies creating gaps to be mended. So Africa has used calculating instruments in the past, and is able to use the modern version with equal intensity.

Q: What was the process that enabled you to bring Internet technology to, first, the West African region?

In 1988, I started Network Computer Systems (NCS), a networking company. By 1994, NCS had become the first company in West Africa to operate Internet services by first using international dial-up to the Public I.P. Exchange Ltd (Pipex) in the UK. Thereafter, we focused our energies on sharing the knowledge with other operators in Africa, to accelerate the presence of the Internet in the sub-Saharan region.

Q: How important was or is the role of cooperation and information sharing?

After NCS had acquired the technology in 1994, it shared with colleagues and proceeded to organise, to teach and to share. These efforts culminated in the formation of the African Network Operators Group (AfNOG). AfNOG is a forum for the exchange of technical information, and aims to promote discussion of implementation issues that require community cooperation through coordination and cooperation among network service providers to ensure the stability of service to end users.

The goal of AfNOG is to share experience of technical challenges in setting up, building, and running Internet Protocol (IP) networks on the African continent. AfNOG held its maiden event in 2000, but the AfNOG annual event has now become a major meeting place of Africa’s technical community, where global partners meet to share ideas.

Being a community, our commitment is to support each other. AfNOG remains the principal vehicle of training, coordination, and exchange of technical information.

Q: What were some of the challenges you faced in trying to establish and expand Internet access in Africa?

I did this work in the “can do” era that prevailed under the government of the former Ghanaian president, Jerry Rawlings, in 1993 and did not experience any undue corruption challenges. The principal challenge was the lack of technical capacity of professionals to man the complex systems.

However, we were able to overcome that challenge by establishing a Department of Computer Science at the University of Cape Coast where we started training university graduates in computer science. Subsequently, as a teacher and researcher, I continued to train and nurture researchers in computer network sciences at NCS.

Q: How were you able to overcome the challenge of there being a lack technical capacity among professionals to man the complex systems?

I initiated the establishment of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Cape Coast to build a culture of training graduates in computer science. Subsequently, as a teacher and researcher, I continued to train and grow researchers in computer network sciences at NCS.

I then focused on building an industrial concern to lead the way in the introduction of technologies into West Africa. The establishment of NCS introduced the Internet to the region in 1993 and 1994.

Q: Was President Rawlings supportive of your efforts?

Yes, former President Rawlings got to know about it before we went operational after the research and development phase. His era had a pro-Ghana “can do” attitude, so his administration embraced the technology. In fact, Rawlings, a former Flight Lieutenant, had one of the pilot user accounts and he was fond of using it, especially with his interests in aviation and model airplanes.

Q: How are you and your colleagues proposing to increase Internet availability, especially in rural Africa?

There needs to be an agenda for the African continent if the digital divide is to be conquered; this will include items such as infrastructure development, information economy management, and institutional development, as well as strategic directions and priority applications. International connectivity settlements and Internet dispersion within the country and regionally are extremely important for infrastructure development.

Furthermore, in spite of the fact that nearly all African countries are now fully connected to the Internet via Internet Service Providers (ISPs), a policy is needed to normalise the costs of ISP services in order to reduce the undue burden on the emerging countries that are performing a global service. Also, very high bandwidth information highways and exchanges must be constructed to interconnect all key towns in each country and also, every capital city on the continent.

Q: What else does Africa need to do?

There needs to be proper management of Africa’s information economy. Without a strong local economy, it is very difficult for developing countries to compete effectively in the global market because several of the required services – logistics, quality control, return policies, and the like – may not be on par internationally. Therefore, African countries should have policies that support local market development as a priority.

Furthermore, strong local markets benefit key applications such as e-commerce and e-governance. Liberal and competitive markets are important in stimulating needed investment in the telecoms market.

Q: What should be the role of African governments?

Industry development is one area where African governments can play a key role. It is a fact that a good amount of the technology components essential for implementing networking infrastructure are manufactured by a few multinational corporations who are not currently operating in African countries. Hence, African governments should devise policies and programmes that attract these multinationals to invest and manufacture some of the products in Africa.

Q: In 2008, a meeting organised by the International Telecommunication Union in Kigali, Rwanda, about bringing broadband connectivity to Africa strongly emphasised that Africa’s telecoms needs to be deregulated and opened up to market forces to allow individual states to bring broadband and ICT into their countries. Is it a point of view you share?

Yes, although one may go a little further from our computer networking orientation. After you have got the basic broadband infrastructure, things have to go through it and that is where the networking community comes in.

For example, issues such as shutting down ISPs are stupid things of the past. So are reversals of privatisation policies – they are really bad because they affect investor confidence. In general, one needs to accelerate things such as e-commerce, telephony, etc, so that we can get traffic going on these systems. And in so doing, we can begin to have a more established share of our information society and feel some sense of ownership and drive towards achieving that established share.

Q: You advised African governments that the continent would need at least two million locally trained ICT experts annually if Africa is to overcome the challenge of ensuring sustainable economic development through the use of the Internet. How did you arrive at such a figure? Has this target been achieved? Why or why not?

Africa has done well on the ICT awareness and use training aspect, but has not done so well with training engineers and computer scientists. Sustainable economies that use ICT and the Internet have a high percentage of university graduates and an equally high percentage of scientists and engineers. Thus training 10 million ICT professionals is to ask to produce less than 2% of the population, which is a modest goal.

Q: How has the access of computer/Internet resources transformed a particular African community? In other words, a techno-liberated success story?

The introduction of full Internet connectivity to Africa was achieved by engineers trained at ISOC Network Technology Workshops and subsequently by AfNOG’s networking workshops. One would agree that the introduction of the Internet has transformed Africa, and it came about from acquiring technical knowhow.

Q: You have controversially said to critics that affordable computing in Africa is more important than the basic necessities of life such as food and clean water. Explain?

Take for example, supplying water services in Africa on a large scale. This requires education as well as technology, which also includes computing network resources. That is how consumers are created. But it is the absence of this capacity that creates the vicious cycle of dependence alongside failure of service delivery.

So, long discussions on whether we should take water or food are really immaterial in my opinion. What we are trying to do is to increase the penetration of Internet usage from the almost 5% we have currently in sub-Saharan Africa to the rest of the 95% who are without it.

Yes, Africans need food, water, etc. but we also need affordable computing, which will help us to feed ourselves, as well as provide other basic necessities such as education, housing, sanitation, and in so doing help bring about socio-economic development.

Q: Let’s take the issue of healthcare. Has Internet access in Africa helped the poor to get to clinics and affordable or free medicines?

With an African Internet user penetration of 4.8%, one can hardly boast of Internet access having helped the poor to access clinics or healthcare. However, the role of the Internet should not be ignored since many clinics and hospitals in Africa now have email addresses and their employees have become Internet users.

Furthermore, there is also the Telemedicine Task Force for Africa initiative, where the potential of satellite telecommunication technology was demonstrated as a tool for supporting healthcare systems in sub-Saharan Africa. It aims at extending e-health on the continent. This is becoming the norm as the Internet is being more widely used for healthcare purposes.

Q: In 2002, you wrote a report called “Africa’s Digital Rights”. It seems that you feel that “digital rights” are strongly related to human rights and development. Why?

The impact of the gap between the haves and have nots in a knowledge industry may be devastating. Digital rights are not too far away from the right to education. I consider it as a right that can reduce poverty by building knowledge-based societies.

Q: Do you believe that in the new information-intensive global economy, Africa is heading towards a future of poverty and oppression? Is this why you champion ICT for Africans so strongly?

I rather believe that Africa is about to miss a great development opportunity in much the same way Africa lost on the industrial revolution, unless serious and truly committed efforts are made by Africa to address the rapid expansion of the gap. I appreciate the danger; and I am making the best effort to get genuinely committed folks to increase activities on the ground.

I believe that Africa is about to miss a great development opportunity unless serious and truly committed efforts are made by Africa to address the digital divide

Q: What are some of the dangers of the ICT revolution?

I believe that the failure to utilise ICT in poverty reduction would lead to gross inequalities that would fuel global unrest and threaten peace and harmony. And for those who may question the basis for this caution, even though the entire African community is at risk, nonetheless important sub-groups may be identified. These include rural communities, the urban poor, women, youth, the disabled, orphans, senior citizens, street hawkers, workers, and Small and Medium Enterprises.

The need, therefore, is to define specific programmes in ICT that focus on these groups. The indigenous, on the whole, are an at-risk group which needs special attention. The ICT programmes that focus on these groups should be clearly defined, identified, and addressed as part of the Global BDD Agenda.

Q: How is Internet access and mobile phone technology in Africa narrowing the digital divide?

Regarding the Internet, one might say it is amorphous. In some regards, we have made gains and in other regards we have failed. Groups in metropolitan areas with a good education have certainly benefited in the narrowing gap, but that is not widespread.

At less than 5% Internet user penetration, Africa cannot boast of having narrowed the gap between the developed and developing world. But we can claim that we have achieved that in a decade from scratch, and that is a good momentum for Africa. We see promise in the convergence of mobile phone technology and the Internet.

Q: Explain what you mean when you say Africa needs not only Internet users but also Internet entrepreneurs?

The Internet is a very effective means of increasing economic growth. It improves the supply of services as well as access to the services, and the developing world would want to participate in both sectors. Africa should establish businesses that develop applications, resources and services to serve the domestic and international markets. An economy made up principally of users of internationally supplied Internet services would be at a disadvantage.