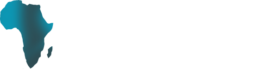

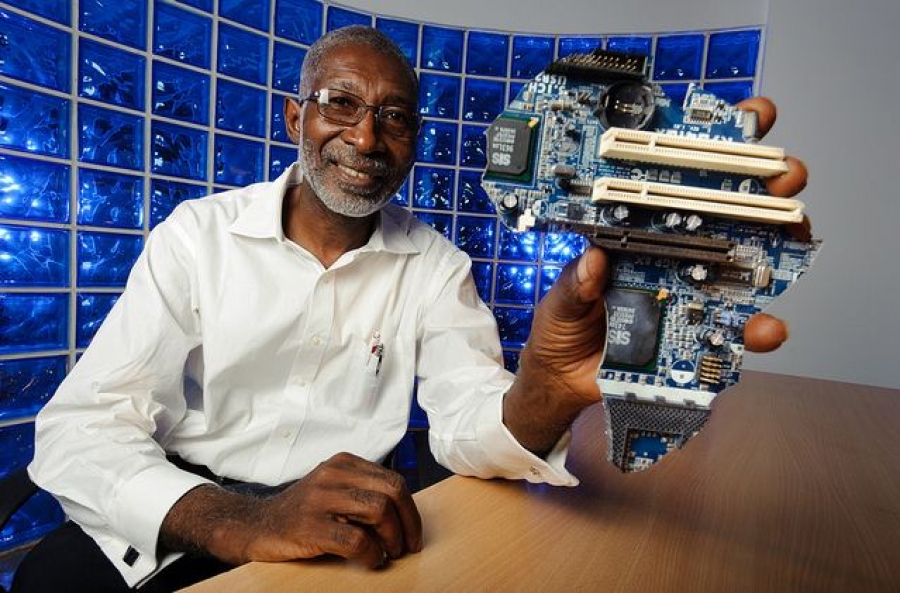

ALUMNI PORTRAIT: DR. NII NARKU QUAYNOR ’72 TH’73 – AFRICAN INTERNET PIONEER

Nii Narku Quaynor ’72 Th’73, the “African father of the Internet,” navigated academic, industry, and government spheres to conquer first doubt and later intense resistance to his pioneering efforts to connect a continent.

One of the first computer science PhDs in sub-Saharan Africa, Quaynor was instrumental in the development of Africa’s Internet infrastructure, establishing the first Internet connections, founding key organizations, and working with governments and agencies to promote information communications technology. He was the first African board member at the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and established the computer science department at Cape Coast University in Ghana, where he still holds a professorship. In 2012, Quaynor was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame.

Having left Dartmouth in 1973 to pursue his doctorate in distributed systems at State University of New York at Stony Brook, Quaynor recently returned to Hanover for the first time in 45 years. He presented a Jones Seminar on his early Internet experiences and a talk about the domain name system. ThayerNews caught up with him during his visit.

He recalled how difficult it was in the early 1990s for the people of West Africa to see the value of the new information superhighway.

“They didn’t know anything about computer science, so you had to educate everybody,” he says. “Policymakers didn’t understand. Industry didn’t understand. Academia was struggling to catch up. It was not a very easy place to work on this new technology, but I still tried.”

Quaynor helped people grasp the technology on their own terms, he says. To illustrate, he pulls out his mobile phone and calls up an app he built to show how an ancient board game acts like a computer. Oware, a two-player strategy game that belongs to the Mancala family of pit-and-pebble games, is popular in Quaynor’s native Ghana. By moving pieces on Quaynor’s virtual Oware board, users can perform addition and even multiplication problems, similar to an abacus.

“I demonstrated that it’s actually a computer, it’s a calculating instrument, but people don’t know how to use it, so I wrote a book on it, and then I wrote the program that uses it to teach people,” Quaynor explains. “I’m trying to connect with them, so I take a game that they are familiar with, and I tell them, this is a computer, and then they understand.”

Quaynor then opens the mobile app he developed to teach Ga, a disappearing Ghanaian language; his voice plays through the phone, repeating pronunciations. This app employs computer science tools he learned at Thayer School from Professor Miles Hayes, whose encouragement long ago helped propel Quaynor toward his many achievements, he says. Looking back, Quaynor credits his exposure to the liberal arts for preparing him to communicate across various fields and contexts, and to use his technical skills to help preserve his culture.

“It’s largely because of Dartmouth, to be honest, that I don’t see computing as computing,” he says. “I see computing as something that can solve our larger issues.”

For decades, Quaynor has been focused on the issue of narrowing the digital divide. After graduate school, he worked with Ghana’s Cape Coast University to establish a computer science department in 1979, but he didn’t return to Ghana full-time until 1993. In the meantime, he worked at American computer giant Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), where he designed CPUs. He spent his off time traveling to developing countries around the world, teaching courses to physicists.

“I was obsessed with making computer science available in the developing world, but I was doing it through physicists, teaching them how to use microprocessors to do measurements,” says Quaynor. “I spent five, six, or more years doing that, because I was really obsessed with the digital divide, which led finally to me deciding to go back to Ghana.”

By 1994, Quaynor’s company, Network Computer Systems (NCS), had become the first Internet service provider in West Africa. At first, he says, as scholars and policymakers experimented with free online accounts, doubts gave way to enthusiasm, leading to the formation in 2000 of the African Network Operators Group (AfNOG), a forum for collaboration among African ISPs.

But just a few years later, says Quaynor, NCS began to face an intense and sustained resistance to Internet adoption that ultimately led to the company’s demise in 2003. Quaynor regrouped at Cape Coast University and in 2008 launched Ghana Dot Com (GDC). GDC is a networking and IT consulting firm, an ICANN-accredited domain name registrar, and a training center. Quaynor serves as chairman and instructor, teaching new technologies, such as blockchain, to help build a technical workforce.

Today, total Internet penetration across Africa remains at about 30 percent. To keep pace with an increasingly global society and prevent isolation, Africa still has a long way to go, says Quaynor. But he’s optimistic, he says, because Africa can learn from the mistakes of the rest of the world as it continues to build its digital future.

“We’ve seen the ills of what can happen,” he says, “so those of us who are working in Africa should do it properly by not repeating those mistakes.”

—Kristen Senz

April 2018